There are several different types of residuals in a Cox proportional hazards model. One of them is the Schoenfeld residuals. They are used to test the proportional hazards assumption.

To understand the Schoenfeld residuals, you need to first recall the partial likelihood that is used to estimate hazard ratios in Cox regression model.

Likelihood

The likelihood function is the foundation for most statistical methods. You are trying to estimate some unknown parameters \(\theta\) and each subject has a density function that is related to data measured on that subject and the unknown parameters.

Here’s a simple example. Assume that there is no censoring and that the event time is exponential with a scale parameter \(\lambda_0\) for the control group and a mean parameter that is \(\lambda_0+\lambda_1\) for the exposed or treatment group. The data in this case is the actual event time Y_i and an indicator variable X_i that is equal to zero for the control group and 1 for the exposed group.

To simplify things, I will let

\(\lambda=(\lambda_0, \lambda_1)\)

\(Y=(Y_1, Y_2, ..., Y_n)\)

and define X similarly.

The density function,evaluated at the observed survival time is

\(f_i(Y_i, X_i, \lambda)=(\lambda_0+\lambda_1X_i)exp(-Y_i(\lambda_0+\lambda_1X_i))\)

We want to find “good values” of \(\lambda\), ones that are associated with large (and therefore more likely) values of the density. The maximum likelihood estimate is the value of \(\lambda\) that maximizes the products of all these densities.

Let’s make up some simple data for this example. Let Y=(3, 5, 1) and X=(0, 0, 1). The likelihood function in this simple case is

\(L(\lambda, Y, X)=\lambda_0 exp(-3 \lambda_0) \lambda_0 exp(-5 \lambda_0) (\lambda_0+\lambda_1) exp(-(\lambda_0+\lambda_1))\)

It is often simpler to maximize the log of the likelihood. There are several reasons for this. First, a product of densities turns into a sum of log densities and sums are easier to work with than products. Second, many densities have an exponential function built into them and that function “disappears” after taking logs. I will use lower case for the log likelihood.

\(l(\lambda, Y, X)=log\lambda_0 - 3 \lambda_0 + log\lambda_0 - 5 \lambda_0 + log(\lambda_0 + \lambda_1) - (\lambda_0+\lambda_1)\)

or

\(l(\lambda, Y, X) = 2 log\lambda_0 - 9 \lambda_0 + log(\lambda_0+\lambda_1) -\lambda_1\)

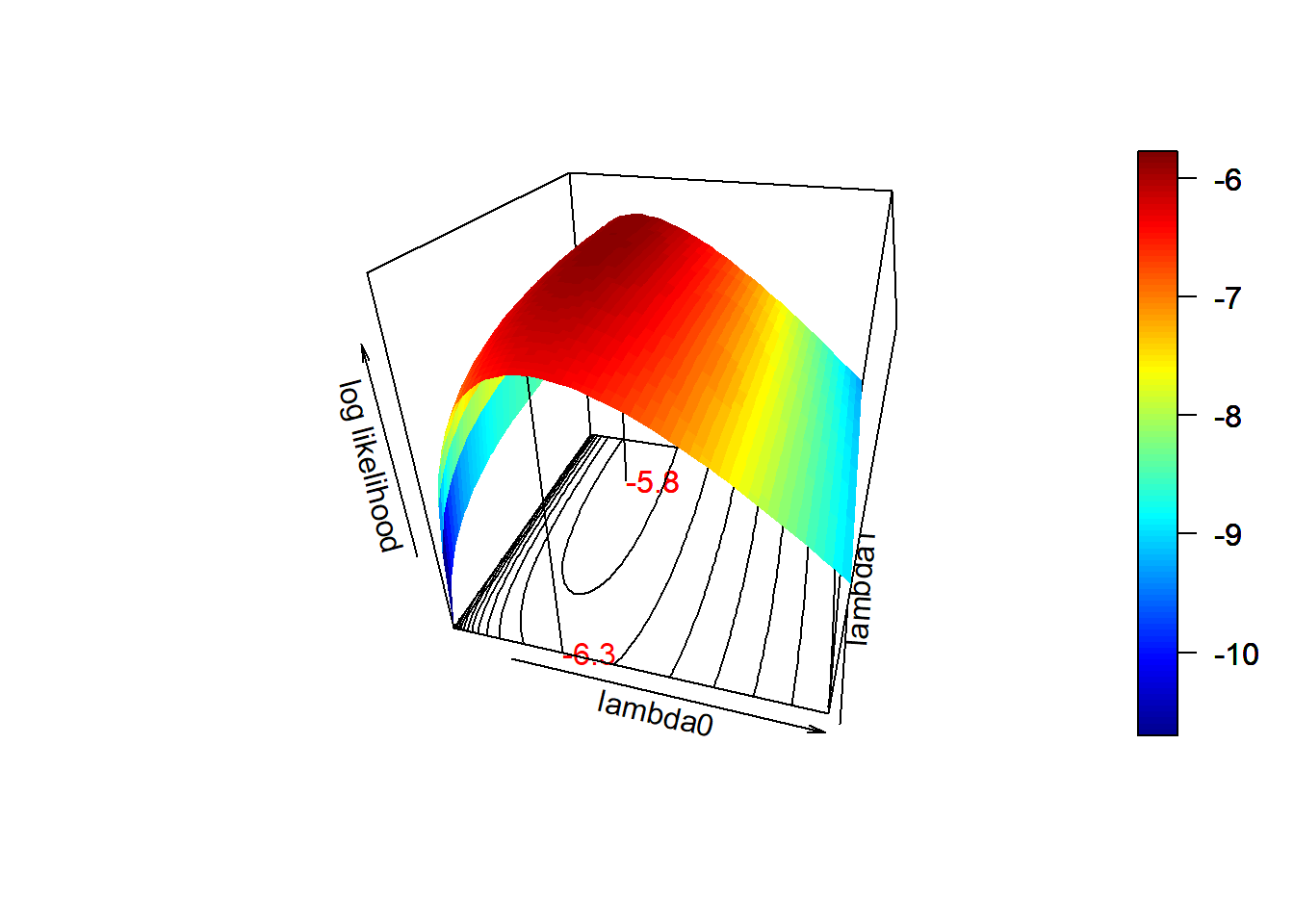

Let’s graph this function.

This is a bit lopsided, but not too far off from a three dimensional equivalent of a parabola. There are several interesting things you can do with the log likelihood.

First, you can find values of \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) that maximize this function. This is the maximum likelihood estimate.

In this example, the maximum value occurs at \(\lambda_1=0.33\) and \(\lambda_2=0.5\). (Note: double check this!!!)

Second, you can compare the log likelihood at the maximum to an alternative hypothesized values for \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\). If the log likelihood is a lot smaller, then you should reject your hypothesized values. If the log likelihood at the hypothesized values is only slightly smaller, then you should accept these hypothesized values are reasonable. This is the maximum likelihood test.

For example, you can hypothesize that \(\lambda_2\) is zero. You let the value of \(\lambda_1\) be unconstrained. This is effectively calling the two groups identical.

The maximum value for the log likelihood is -5.7741614. If you set \(\lambda_2=0\), the log_likelihood is -6.296429. Since these values are close, you can consider the hypothesis to be reasonable.

You can also look at the partial derivative of the log likelihood at the hypothesized values. If the partial derivative is close to zero, that means that you are pretty close in log likelihood terms to the maximum likelihood, since the partial derivatives at the maximum have to be zero. In such a case, you can accept your hypothesized value as reasonable. If the partial derivative is large, you have a steep uphill climb until you reach the maximum likelihood. You are nowhere near the maximum and should reject the hypothesized value as unreasonable.

In this example, the slope is approximately 0.05. Since this value is small, you can accept the hypothesized values as reasonable.

Finally, you can compute the matrix of second partial derivatives at the maximum likelihood estimate. If this matrix is large, that means that the log likelihoods fall off rapidly once you move away from the peak. You can conclude that your maximum likelihood estimate has a lot of precision. Conversely, if the matrix of second derivatives is small, that means that the likelihood goes away from the maximum quite slowly for a large distance. In this case, your maximum likelihood estimate has poor precision.

To find out where the maximum occurs, take the first two partial derivatives and set them equal to zero.

\(\frac{\partial /l}{\partial \lambda0} = 2/\lambda_0 -9 + 1/(\lambda_0+\lambda_1) = 0\)

\(\frac{\partial /l}{\partial \lambda1} = 1/(\lambda_0+\lambda_1) - 1 = 0\)

The second equation tells you that

\(\lambda_0+\lambda_1=1\)

Substituting that into the second equation gives you

\(\lambda_0=0.25\)

and then you can show that

\(\lambda_1=0.75\)

17772f400cc3acd5b2c61623fc3cf2c98df50124

\(L_i(\beta) =\frac{\lambda(Y_i\mid X_i)}{\sum_{j:Y_j\ge Y_i}\lambda(Y_i\mid X_j)} =\frac{\lambda_0(Y_i)\theta_i}{\sum_{j:Y_j\ge Y_i}\lambda_0(Y_i)\theta_j} =\frac{\theta_i}{\sum_{j:Y_j\ge Y_i}\theta_j},\)

where

\(\theta_j = exp(X_j \beta)\)