You find yourself using what, to you, is a new statistical approach, multiple imputation, and you’re uncertain about how to approach it. You’re not sure what options you should be picking and you don’t want to rely on your software’s default choices. You may also be insecure about using the right words to describe your approach in the methods section of your research paper.

Finding examples that have already appeared in the literature is one way to start. I call it the lemming school of research (if all your friends jumped off a cliff, would you jump off too?).

That sounds pejorative and maybe it is. You run the risk of repeating a collective blind spot among researchers and reinforcing bad habits.

But most of the time, the lemming school makes sense. There is safety in numbers. If you adopt an approach that frequently survives the peer-review process, you increase the chances that your paper will survive the peer-review process by adopting the same approach.

So how do you find good examples of published research that use a new and exotic statistical methodology? It’s not easy, but you have one advantage on your side. You want a search that is specific, but not necessarily sensitive. A specific search is one that doesn’t have a lot of false positive results. You don’t have to search through a long list of irrelevant publications to find one or two publications that can really help you.

This is contrast to the sad soul who is running a systematic overview. If you were running a systematic overview, you would need to run a sensitive search, one that has very few false negatives. The worst sin in a systematic overview is missing an important and relevant research study. You need to comb through a long list, often in the thousands, of publications to be sure that you have everything. You lose a lot of time sorting through a big haystack just to find a few needles.

So let’s talk about how to do a good search. I am going to focus on PubMed because most of my searching that I do involves publication in the medical field. But almost all of the approaches shown here will work with other search engines.

Suppose that you are running a multiple imputation model for the very first time. Admit it, you’re more than a little bit nervous. You could go into PubMed and do a straight search on multiple imputation

to see what pops up. But each medical and scientific discipline has its own perspective on how to apply a new technology. Each discipline has its own language for describing things. So try to limit your searches to publications in a particular discipline.

Let’s assume that you’re working with a group of pediatricians who are studying exercise-induced asthma. So include the “asthma” and “children” in your PubMed search:

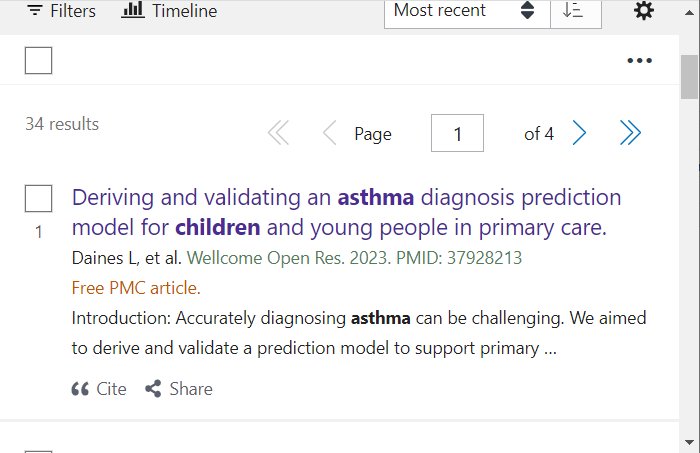

When I ran this search recently, I got 34 results and the very top one

looked pretty good. Click on the link to find out that the abstract includes the following sentence:

- “Multiple imputation was used to handle remaining missing data.”

Ding, ding, ding, ding, ding! There’s a bonus! This publication has full free text at PubMed Central (PMC) and at the journal’s website. Click on either link to find a few more tidbits in the paper itself. The authors only used multiple imputation for variables with less than 40% missing values. You weren’t really sure how much missingness was too much to tolerate and now you know where to draw the line: trash any variables with more than 40% missingness.

The news gets even better. The authors provide a reference justifying the use of a 40% cut-off! Steal this reference and put it in your own bibliography. Don’t forget to check for typos. You would be amazed at the number of errors in bibliographies that get propogated when one random error gets into the literature.

Restricting your search to full free text papers

There’s nothing more frustrating than identifying a good paper and finding out that it is stuck behind a paywall. The third article in my list

is published in a journal that demands 52 dollars to allow you access and even then, the access is only for 24 hours. Highway robbery!

Remember, though, that your goal is a specific search and not a sensitive one. If you miss out on an article that is stuck behind a paywall, just keep looking for one that is not behind a paywall.

PubMed has a checkbox on the right hand side of the search results that will allow you to only include papers with full free text. This is a very nice option that is not available with most search engines.

Google Scholar has an interesting answer to the paywall dilemma. When you find an article that is trying to extort you, you may have an out. Google Scholar has a small link at the bottom that reads “All xx versions” and if there are multiple versions, maybe one of them will offer the full free text. This might be a pre-print or a version on the author’s website. Do take care not to abuse this. Some websites will share the full free text in violation of the journal’s copyright restrictions. As much as I hate paywalls, publishing full free text outside the paywall without the journal’s permission is theft of intellectual property.

Improving your search specificity

Sometimes, the list you get back with PubMed or other search engines is a disaster. Suppose you were interested in papers using the R package MICE for multiple imputation. A PubMed search substituting the word “MICE”

yields thousands of papers and almost all of them are animal studies.

Spelling out the acronym helps in this case. You might also try using synonyms that don’t have as many ambiguous meanings. If “neural network” doesn’t work well, try “deep learning” instead.

Try adding an extra adjective to restrict your attention (“artificial neural network” instead of just plain old “neural network”).

Most search engines have Boolean logic that you can use to weed out the false positives. Use the keyword “NOT” to exclude false positives (“mice NOT animal”). Most search engines will provide links with any of the terms in your search. PubMed is an exception, but most search engines will implicitly use the “OR” keyword between each term. Use the keyword “AND” to be more restrictive (“multiple AND imputation”). Better still, use quotes to insure that the two terms appear right next to each other (“multiple imputation”).

What about non-medical articles

PubMed is the best game in town if you are in the market for articles from medical journals. It covers a very broad swath of journals. It has very sophisticated search features (more than can be covered here). It has nice tools for adding references to your favorite bibliographic source. It does cover some scientific journals (especially biology) reasonably well, but not others. And it has very limited coverage of journals in other areas such as mathematics, engineering, or business administration.

Google Scholar is a nice alternative if you are after those types of journal articles. With the search engine power of Google behind it, you can find journal articles from all sorts of disciplines. As noted earlier, it will find links to multiple versions of an article, not just those from the official journal site.

There has been an explosion of pre-print servers where researchers can publish their works before they are sent to peer-review. These pre-print servers specialize in a variety of narrow disciplines, such as Paleontology and Linguistics, which may or may not be an advantage. Now, you may prefer to wait until the article has survived peer-review, and the good news is that most articles in a pre-print server stay on, even after they appear in a journal. Most journals have resigned themselves to the reality of pre-print servers, even the ones with outrageously priced paywalls.

If you want a really narrow source, go directly to your favorite journal (I really love BMC Medical Research Methodology) and conduct your search there. Every journal has a robust search option. You might not get as many hits, but the ones you do get are likely to be on target.

Where more work is needed

All the above is well and good, but the one thing I wish for is better sharing of the data underlying all these analyses. There are many calls for sharing research data. Some disciplines do well at this (genetics, is a good example), but many others do not.

There are issues, especially privacy concerns, that need to be addressed before sharing your research data. These can be managed in most settings, but often researchers do not even try. When they do share their data, it is often provided only at an aggregated or summary level. What does get shared is usually poorly documented.

In spite of this, journal articles are a good resource if you want to see how others approach new and innovative statistical methods. Finding the right examples is not always easy, but the reward is worth it.