This is part of series of articles on how to set up and use version control on your computer. There are many systems for version control. In these articles, you will use a program, git, and a repository, github.

This article explains how to download git and set up a local project. It is loosely based on a video provided by the nice folks who program git. If there are problems on this page, blame me and not them.

Is git already on your computer?

You may already have git installed on your computer. It depends on whether you are using a Mac, Windows, or Linux system and also on what software you may have installed already that uses git.

To check this, go to the command line interface (CLI). Go to the command line interface (CLI). On a Windows computer, there are several ways to do this. Look for a program called “Command prompt” or an icon like this.

At the CLI, type git --version. If it runs, it shows proof that you already have git on your computer and it identifies which version of git you are running. Any version of git is fine for a beginner.

If you get an error message (like git is not recognized) then look a bit further. Look in the folder or folders that store programs on your computer (for example, c:/Program Files and c:/Program File (x86) on a Windows system) for a folder named Git. If you find it, see if you can run git after changing directories. If this works, you need to modify your path so that your computer can find git, even when in a different folder.

If you need to install git

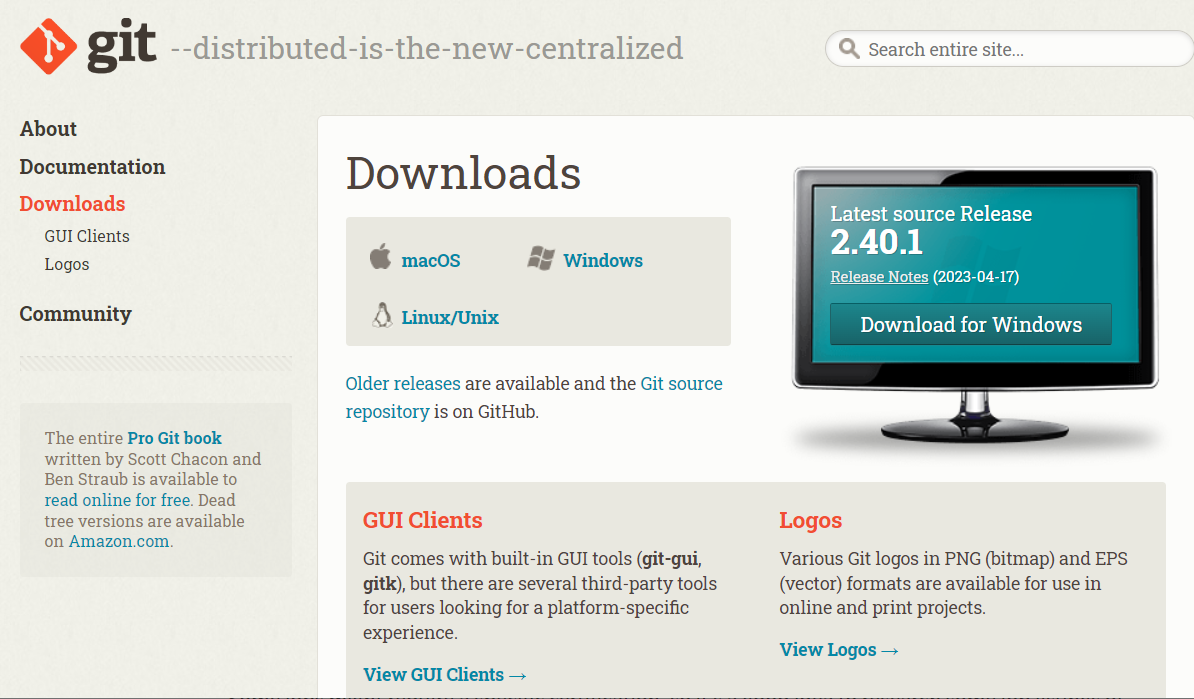

So if you cannot get your computer to run git, or you are impatient and don’t want to run the checks suggested above, go to the official download site for git

and identify your computer system.

Click on the appropriate link and run the downloaded files.

Go to the command line interface (CLI). On a Windows computer, there are several ways to do this. Look for a program called “Command prompt” or an icon like this.

At the CLI, type git --version. If it runs, it shows proof that you installed git correctly and it identifies which version of git you are running.

Typing git all by itself will show you some of the options available to you with this program. Do not worry that you don’t understand many of these options now. Some you will learn in later web pages in this series. Others will not be important until you start doing advanced work with git.

Try exploring some of the help guides. You can get a list of all guides with git help -g

Take a look at

- everyday,

- faq,

- glossary, or

- tutorial

If you understand less than 1% of what is in these guides, you are normal.

Warning

In your explorations, you may sometimes be placed inside an editor, vi, that comes with the CLI. If you find yourself “stuck” and unable to type any CLI commands, try typing the single letter “q”. If that doesn’t work, close the CLI and then re-open it.

Setting up the configuration file

You should store information about yourself in the git config files. To get a list of the current configurations, type git config --list.

Add your name and email address with

git config --global user-name 'First-name Last-name'

git config --global user-email 'email@umkc.edu'

Rerun git config --list to show these additions.

Identifying your name and email is important if you work with a team of other programmers. This will allow everyone to see who is making what changes where and when.

The configuration files are hierarchical with information stored at the system, global, and local level. Information stored at the system level is applicable to all users on a computer. Information stores at the global level is specific to you, a specific users on the computer. For some computers with a single user, there may not be any practical distinctions between the system and global levels.

The local level stores information specific to a particular directory on your computer. This will also be synonymous with a particular remote repository (more details about remote repositories will come later).

If there are discrepancies, the local level takes priority over the global level and the global level takes priority over the system level.

Don’t worry too much about these distinctions for now.

Initializing a project

A project in git is a folder and all the subfolders that you plan to use for a particular programming or research effort. What constitutes a project is difficult to answer. You might create one massive folder that contains everything that you do and track that using git. Or you might create hundreds of folders and track each one separately. You should consider something between these two extremes. The recommendation in Wilson et al, Good enough practices in scientific computing, is that if two research efforts have no files in common, consider them as separate projects. If they have more than 50% of their files in common, consider them parts of the same project. In between 0% and 50%, use a bit of common sense.

Several sources I have read also stress that you should name the projects after the type of work being done and not name them after the person or department doing the work. In most organizations, the people who work on a project will change over time. So describe the project as “X inactivation” instead of “Genetics department”.

AS you start out, it is probably better to have many narrowly defined projects than fewer broadly defined projects. If you are taking one of the classes I teach, it is better to have a separate project for each module in the class rather than one module for the entire class. When you get a job with a large company, they may have more guidance about this issue.

Move to the folder where you want to store your first version controlled project. A logical location would be under your documents folder. On my computer, you would move to this folder by typing cd c:/Users/steve/Documents though it would be different on your computer. Then on the CLI, type

git init project1

where project1 could be any name you like.

This creates an almost empty folder with some bookkeeping information stored in a .git subfolder. You might want to peek at some of the files in this folder. They are all simple text files, so you can open them in notepad or your favorite text editor.

Creating and updating files

Most programming projects will have a subdirectory structure with data stored in a data folder, programs stored in a src folder, and output stored in a results folder. Go ahead and set these up, if you like. For very small projects, you may not need this.

But every programming project, big or small should have a README file. Sometimes this file has a .txt extension, but I recommend that you use an .md extension for this file.

So create a file, README.md, using notepad. For now, keep the file short and simple.

## Project 1

This is a project to test the features of version control.

Save the file. Now type

git status

on the CLI. You will see that git has noticed something. It warns you that README.md is “an untracked file” and recommends that you use git add to track it.

So, type

git add README.md

on the CLI. Now if you check in with git status, you will see that this file is in the list of changes to be committed. This is sometimes called staging a file.

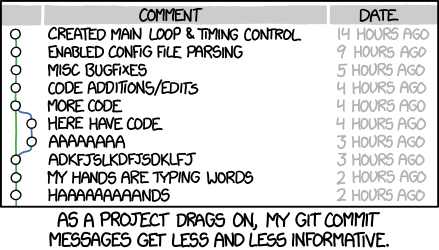

You tell git to update the project using the commit command. Every commit command requires at least a brief message. When you do this regularly, you create a historical record of how your porject has changed over time.

Scott Munro, author of the XKCD comic strip, has a humorous take on these messages.

Your first message can be something simple like “Initial commit” or “Starting new project”. How you define later commit messages will depend on what the others on your research team want. If you are working alone, think about using messages to help build a changelog file.

Wrap things up with

git commit -m "Initial commit"

If you want to continue, take a look at git-local-updates.