This is part of series of articles on how to set up and use version control on your computer. There are many systems for version control. In these articles, you will use a program, git, and a repository, github.

This article explains how to make and track changes to a local project.

Check status regularly

Get in the habit of checking the status of your project regularly. In particular, do this immediately before and after each individual task. Eventually, you will know instinctively what the status is for your project at any given time, but it takes time.

So, before doing anything else in this module, check the status by typing git status

Create a develop branch

There’s a common saying “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” This applies to programming as well. The worst thing you can do to a working program is to try to improve it and end up breaking it in the process.

There is a series of humorous program documentation comments listed by Nehal Khan on Medium. There are several illustrating the problem of adding new features, such as this one.

/*

* You may think you know what the following code does.

* But you dont. Trust me.

* Fiddle with it, and youll spend many a sleepless

* night cursing the moment you thought youd be clever

* enough to "optimize" the code below.

* Now close this file and go play with something else.

*/

With git, you can fix your programs and add new features without worrying (too much) about breaking things. This makes you a bolder programmer, willing to take chances and try new things.

There are two commands in git that help you be bold: branch and revert.

Every git project starts out with a single branch, usually names either main or master. More recent tutorials on git use main, because of the negative associations with slavery associated with the term master. I will refer to the single branch as main/master to avoid confusion if you are looking at some of the older tutorial materials. You will also sometimes see the main/master branch described as the trunk.

The branch command creates a working copy of your project that you can experiment on. These experiments are safe because they do not change anything on the main/master branch until you are sure that your changes are good. There are many different approaches to using branches. Some systems create separate branches for each new feature that you want to add. These branches are created, quickly tested, incorporated back into the main/master branch, and then removed. Other systems have a single branch where all development work is done.

For simple projects, branching is not needed. A simple revert command (covered later) will provide all the protection you need. Larger and more complex projects, especially team projects, will benefit from branching.

You should spend some time learning about branching, even if you are not currently working on teams or on complex projects.

For this set of webpages about git, I will use a single branch, named develop. I will make changes on the develop branch and then incorporate them into the main/master branch. You may end up in a workgroup that has a more complex branching strategy, but once you understand branching at a simple level, you will find it easy to adapt to more complex levels.

To create a develop branch, type the following into the CLI.

git branch develop

git checkout develop

Now, any changes you make will be on a working copy on the develop branch. The code you have on main/master will still be there if the work on develop makes things worse rather than better.

Update README.md

Let’s make some changes to the README.md file. Open the file in a text editor and add the following lines:

Skills developed

+ Install git

+ Initialize a project

Save the file under the same name. Now go to the CLI and run git status again. Your changes have been noticed by git. On the CLI, stage the file by running

git add README.md

Run git status again. Now enter

git commit -m "Added first two skills to README file"

and run git status one more time.

Revisit the main/master branch

To prove that you have not touched the main/master branch, close your text editor and run

git checkout master

or

git checkout main

on the CLI.

Now re-open the README.md file. You have your original README.md file without the “Skills developed” section.

Close your text editor. Enter

git checkout develop

on the CLI and re-open the README.md file. Now you are back to the file that lists your two new skills.

Make some more changes

Add a couple of more lines to your README.md file listing two new skills you have developed.

+ Create a new branch

+ Switch between two branches.

Save the file and run git status one more time. I won’t keep reminding you about checking your status regularly, but do take the time for this, especially when you are just starting out.

Details about the changes you’ve made

Before you stage the file, you can examine what changes you’ve made with the diff command. Now it seems silly. You just typed in those lines one minute ago. Bear with me on this. When you make a lot of changes to multiple files over a few hours, it helps to remind yourself what changes were made where.

The command

get diff

will show you not just what file or files have changed. It will show you what lines were added, removed, or changed. This will sometimes help you figure out what message to include when you commit your changes.

Go ahead and update the develop branch. First, make sure you are on the develop branch. The output from git status will always inform you which branch you are on. If you are not on the develop branch, enter git checkout develop. Now enter

git add README.me

git commit -m"Added branching skills to README.md"

Compare develop branch to main/master

The diff command will also help you view how two branches differ from one another. Try running

diff develop master

or

diff develop main

to see that the original file on the main trunk has not changed.

Make a third update to README.md

You now know a couple more things. Add the following lines to the bottom of README.md.

+ Display changes to a file

+ Compare changes between two branches

Be sure to stage and then commit your changes. Always include a brief message such as “Describe new skills using the diff command”.

Make a bad change and then revert

You may never do something so stupid that you want to revert back to an earlier version, but I have. So let’s deliberately introduce a problem so you can test how to fix things.

Delete the file README.md. You can do this several ways. On the CLI, just type del README.md.

After you delete the file, stage and commit the changes.

git add README.md

git commit -m"Deleted an unwanted file"

There is a bit of irony here. You stage the just deleted README.md file with the add command.

Now play act a little bit. Shout out “Oh no, what have I done? All my hard work, lost forever!”

But, of course, you haven’t lost anything, because git tracks a history of everything you’ve done. You can get a list of every commit you’ve made with

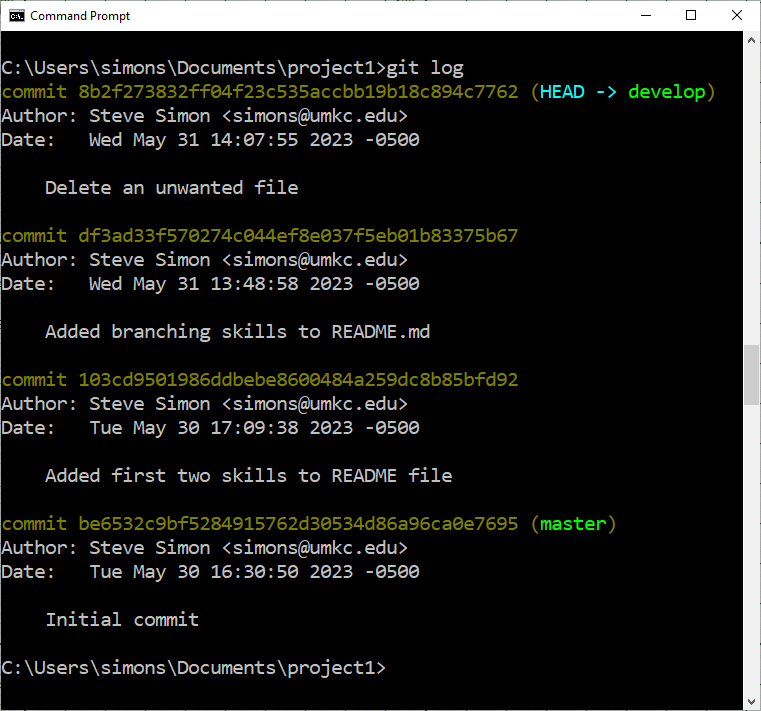

git log

This shows everything you’ve done, on both the master/main and the develop branch. Here’s what it looks like on my computer system.

Your screen will have some differences. If you used different commit messages, of course. But there are some 40 digit hexadecimal numbers associated with each commit. Find the first seven digits of the version you want to go back to and type

git revert df3ad33

but use the first seven digits from your log and not mine.

Merge changes back to main/master

For complex changes, you might want to run a few tests. Once you are satisfied that the changes are safe, you should merge the changes back into the main/master branch.

First, switch back to main/master with

git checkout main

or

git checkout master

Then run

git merge develop

Check that the changes in develop are now reflected in main/master with

git diff develop main

or

git diff develop master

###