I sent out a question to an email discussion group asking about documentation of sample size shortfalls in clinical research. Someone suggested that I google “Lasagna’s Law.” What a great suggestion. Here’s what I found.

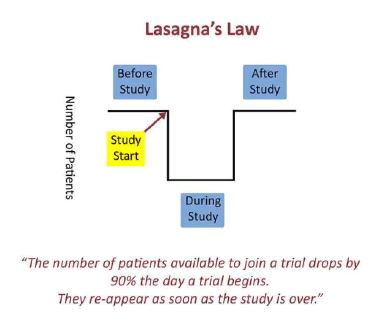

The nicest summary was

It was one of the pioneers in clinical pharmacology, the American Louis Lasagna, who described in 1970 a today’s still well-known phenomenon in clinical trials: The incidence of patient availability sharply decreases when a clinical trial begins and returns to its original level as soon as the trial is completed. For illustration, in 1979 Lasagna commented on a trial where out of 8,000 patients theoretically available just 100 patients in the end participated. Later this phenomenon was popurlarly called Lasagna’s Law. As quoted here.

Several sources point to this article below as the source for Lasagna’s Law, though I could not find it online to verify it.

J.A.L. Gorringe, Initial preparation for clinical trials, E.L. Harris, J.D. Fitzgerald, Editors, The principles and practice of clinical trials, Livingstone, Edinburgh/London (1970)

Another original source might be a book published in 1972 (and republished in 1992)

Spilker B, Cramer JA. Patient Recruitment in Clinical Trials.

Empirical support for Lasagna’s Law was found in

Johannes C van der Wouden, Annette H Blankenstein, Marcus J H Huibers, Danielle A W M van der Windt, Wim A B Stalman, Arianne P Verhagen. Survey among 78 studies showed that Lasagna’s law holds in Dutch primary care research J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(8):819-824. Abstract: “OBJECTIVE: Research in general practice has grown considerably over the past decades, but many projects face problems when recruiting patients. Lasagna’s Law states that medical investigators overestimate the number of patients available for a research study. We aimed to assess factors related to success or failure of recruitment in general practice research. STUDY DESIGN AND SETTING: Survey among investigators involved in primary care research in The Netherlands. Face-to-face interviews were held with investigators of 78 projects, assessing study design and fieldwork characteristics as well as success of patient recruitment. RESULTS: Studies that focused on prevalent cases were more successful than studies that required incident cases. Studies in which the general practitioner (GP) had to be alert during consultations were less successful. When the GP or practice assistant was the first to inform the patient about the study, patient recruitment was less successful than when the patient received a letter by mail. There was a strong association among these three factors. CONCLUSION: Lasagna’s Law also holds in Dutch primary care research: many studies face recruitment problems. Awareness of study characteristics affecting participation of GPs and patients may help investigators to improve their study design.” Paper is behind a pay wall.

Lasagna’s Law flies in the face of Interational Conference on Harmonization Guidelines on research (ICH E6/R1).

4.2.1 The investigator should be able to demonstrate (e.g., based on retrospective data) a potential for recruiting the required number of suitable subjects within the agreed recruitment period.

There are several variations on Lasagna’s Law. Several imply a ten fold discrepancy between the patients available and the number that you can recruit successfully.

In any trial, the incidence of the disease studied will be reduced to 10% of the original estimate. As quoted [here][pct1].

In clinical research the prevalence of any disease falls to about 10% of what you thought it was the day you start to look for cases for your study. As quoted at http://www.bmj.com/content/327/7414/565/reply

As soon as a clinical trial begins, the supply of patients becomes one-tenth of what it was thought to be beforehand. As quoted in Clinical Trials in Neurology by Roberto J. Guiloff.

If the annual supply of suitable patients when the trial is designed is n, when the trial commences it will reduce to n/10. As quoted in Interpretation and Uses of Medical Statistics by Leslie E. Daly and Geoffrey Joseph Bourke.

One quote implies a five fold discrepancy.

As soon as a study begins, the number of patients available instantly drops from a theoretical pool of 100 percent down to 20 percent; as soon as a study concludes, the pool jumps back to 100 percent. As quoted in Reinventing Patient Recruitment: Revolutionary Ideas for Clinical Trials Success by Joan F. Bachenheimer and Bonnie A. Brescia.

Another quote implies a two fold discrepancy.

At the commencement of a study the incidence of the condition under investigation will drop by one-half, and will not return to its former rate until the study is close or the investigator retires, whichever comes first. As quoted in Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model by Terry M. Thernau and Patricia M. Grambsch.

Another offers a ten to three fold discrepancy.

The number of patients who are actually available for a trial is about 1/10 to 1/3 of what was originally estimated. As quoted in Principles of Medical Statistics by Alvan R. Feinstein.

Others imply a general decline without any quantification.

Before a study actually starts at investigative site, there always seem to be more than enough potential subjects waiting in the wings. For some reason, however, it frequently happens that as soon as the trial starts, these potential subjects disappear. When the study is over, there seems, again, to be plenty of suitable subjects. As quoted at http://clinicalresearchzone.blogspot.com/2008/11/louis-lasagna-do-we-still-remember-him.html

A well recognised phenomenon which states that as soon as a clinical trial begins all the subjects who were thought to be suitable for the study disappear. As quoted at http://pharmaschool.co/jargon03.asp?ID=155

The incidence of the disease under study will drastically decrease once the study begins. It will not return to its previous level until the completion of study (if completion occurs before the investigators retire. As quoted in Statistics in the Pharmaceutical Industry by Charles Ralph Buncher and Jia-Yeong Tsay.

Before a study begins, a large number of relevatn patients are available to the investigator. As soon as the study begins, the patients disappear, only to reappear after the study ends. As quoted in Patient Recruitment in Clinical Research: A Guide to Europe by Danielle Jacobs.

A variant, called Munch’s law (be sure to also search for Munch’s law with an umlaut or Muench’s law) uses the previously cited ten fold discrepancy

In order to be realistic, the number of cases promised in any clinical trial must be divided by a factor of at least ten. as quoted in the Dictionary of Pharmaceutical Medicine by Gerhard Nahler and Annette Mollet.

There’s lots of speculation at these sites as to why this overestimation of patient availability occurs, such as very narrow inclusion criteria, high refusal rates among patients, and insufficient resources to approach eligible patients.

A major study of recruitment noted that less than one third of trials held by the Medical Research Council and Health Technology Assessment Programmes finished on time with the required number of participants. 41% (47/114) of the studies had delays to the overall start of recruitment, 63% (77/122) had slower than expected early participant recruitment, and 38% (46/122) had slower than expected late participant recruitment.

Journal article: M K Campbell, C Snowdon, D Francis, D Elbourne, A M McDonald, R Knight, V Entwistle, J Garcia, I Roberts, et al. Recruitment to randomised trials: strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(48):iii, ix-105.

A similar group is sponsoring a new study, though it appears that the results of this study have not yet be published.

Katrien Oude Rengerink, Brent C Opmeer, Sabine L M Logtenberg, Lotty Hooft, Kitty W M Bloemenkamp, Monique C Haak, Martijn A Oudijk, Marc E Spaanderman, Johannes J Duvekot, et al. Improving PArticipation of patients in Clinical Trials–rationale and design of IMPACT BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:85.

Several other resources tried to quantify the extent to which research projects failed to meet recruitment goals.

Successfully recruiting research participants is a key aspect for the success of a research project. However, this is also a difficult part. Therefore, the Quality Committee of the EMGO Institute started an investigation in 2006 to determine to what extent EMGO research projects were able to successfully recruit participants and what the possible determinants and outcomes of successful and unsuccessful recruitments were. Of the 61 research projects included, one third included less than 90% of the needed participants and 60% of the projects had to extend the inclusion period. As a result, at least 22% of the projects exceeded their research budget. In addition, researchers reported to have withdrawn part of the research protocol, to have skipped/unanswered research questions and to have shortened the follow-up period. As quoted [here][ams1].

This study quoted a previous paper that notes over the period 2001-2005 among 113 research projects, 49% included less than 80% of the needed participants.

Almost 90% of trials are delayed, primarily because of patient recruitment problems. Public perception of the clinical trial process and, indeed, the pharmaceutical industry on the whole is largely very negative. As such, patient recruitment can be a lengthy process, and every extra day spent in clinical trials makes a huge dent in profits: pharmaceutical companies can lose out on anything from $600,000 to $8 million. Source for this quote cannot be found.

The one aspect of conducting clinical trials that sites usually spend the most time working on is Patient Recruitment, and yet, statistics show that despite their efforts, reaching enrollment goals per timeline is frustratingly elusive in many studies. The September 2011 volume of Applied Clinical Trials provides the current statistics: "Today, nearly 80% of clinical trials fail to meet enrollment timelines and up to 50% of research sites enroll one or no patients." (Kremidas, J. (2011). Recruitment roles. Applied Clinical Trials, 20 (9), p. 32. Available in [html format][act1]).`

Nearly 90% of clinical trials are completed with significant delays. As quoted [here][vet1].

In 2001, over 85 percent of all completed medical research studies experienced recruitment delays, and 34 percent were delayed for more than one month. As quoted [here][bea1]. This article cites the following two references: 1. Gamache V. Minimizing Volunteer Dropout. CenterWatch Monthly. 2002;1:9-12. 2. Lightfoot GD, Getz KA, Hovde M, Sanford SM, Stepp PM, Vogel JR. ACRP's White Paper on Future Trends. Spring 1999.

Statistics show that despite pharma/CROs efforts, reaching enrolment goals per timelines seem elusive in many studies, The majority (nearly 85%) of clinical trials conducted in the United States fail to enrol subjects within the contract period. As quoted [here][hcl1]. Note that this brochure references [my website][sim1].

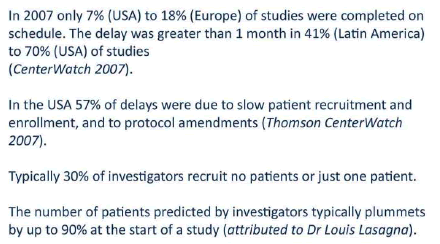

Thompson Centerwatch pulbishes a regular review of the clinical trials industry and several sources have quoted from the 2007 guide.

Images taken from this site

The classic reference on this topic is

Journal article: J A Freiman, T C Chalmers, H Smith Jr, R R Kuebler. The importance of beta, the type II error and sample size in the design and interpretation of the randomized control trial. Survey of 71 “negative” trials N. Engl. J. Med. 1978;299(13):690-694.

and over 96 papers cite this finding. Another classic reference is

Moher D, Dulberg CS, Wells GA. Statistical power, sample size, and their reporting in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 1994;272:122-4. Available in pdf format

I’ll certainly continue searching for more references along these lines and refine the results for incorporation into the draft grant I am preparing for patient accrual.

You can find an earlier version of this page on my original website.