suppressMessages(suppressWarnings(library(broom)))

suppressMessages(suppressWarnings(library(dplyr)))

suppressMessages(suppressWarnings(library(magrittr)))Downward bend

Suppose you want to fit a function that is flat from x=a to x=b and which declines linearly from x=b to x=c.

Here is the formula:

\(f(x) = d - e*(x-b)_+\)

where

\(u_+ = u\) if \(u \ge 0\), \(= 0\) if \(u<0\)

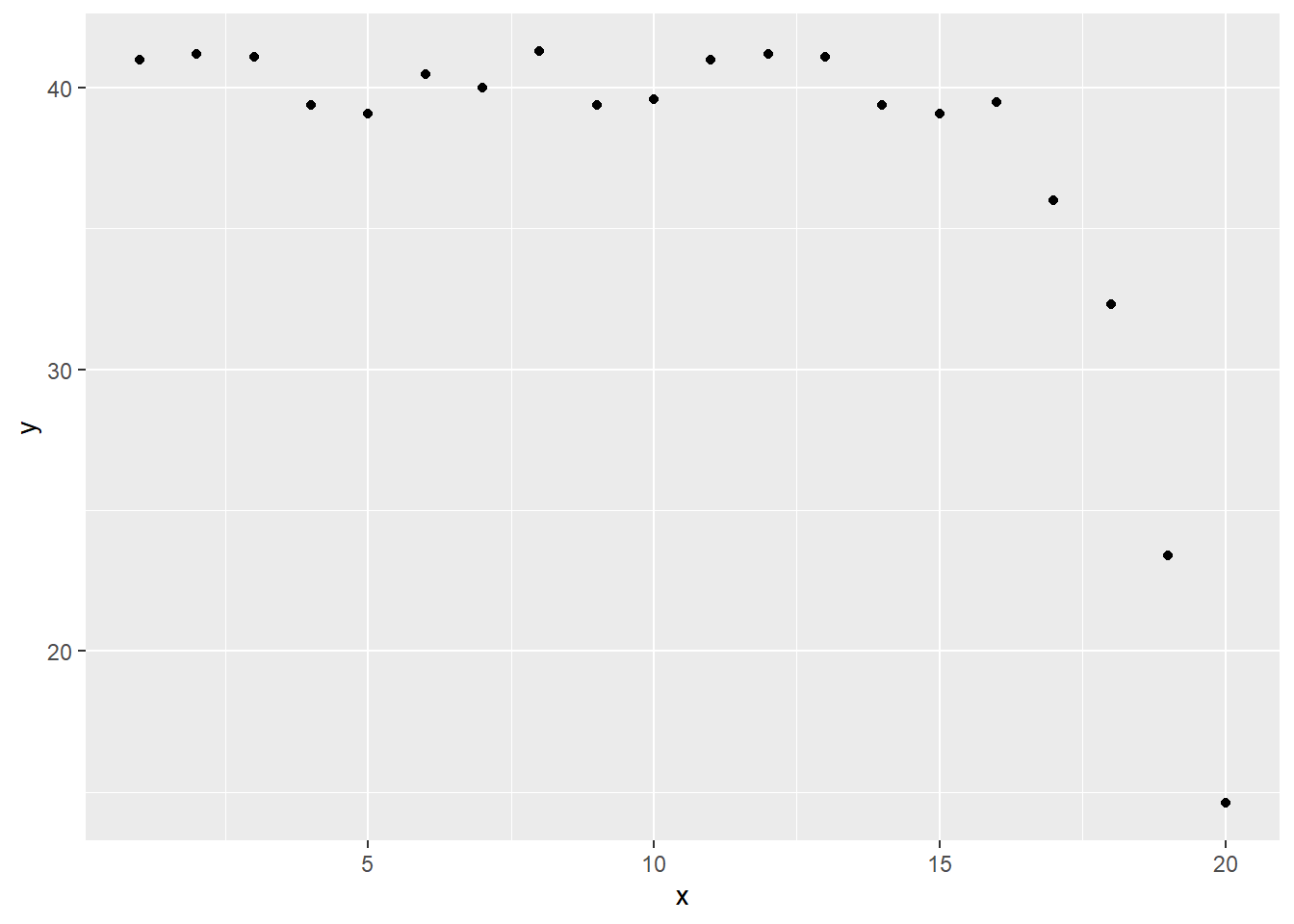

Here is some simulated data for testing this function.

library(ggplot2)

x <- 1:20

y <- c(rep(40, 15), 40-(1:5)^2)+round(rnorm(10), 1)

simulated_example <- data.frame(x, y)

simulated_example## x y

## 1 1 41.0

## 2 2 41.2

## 3 3 41.1

## 4 4 39.4

## 5 5 39.1

## 6 6 40.5

## 7 7 40.0

## 8 8 41.3

## 9 9 39.4

## 10 10 39.6

## 11 11 41.0

## 12 12 41.2

## 13 13 41.1

## 14 14 39.4

## 15 15 39.1

## 16 16 39.5

## 17 17 36.0

## 18 18 32.3

## 19 19 23.4

## 20 20 14.6ggplot(simulated_example, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point()

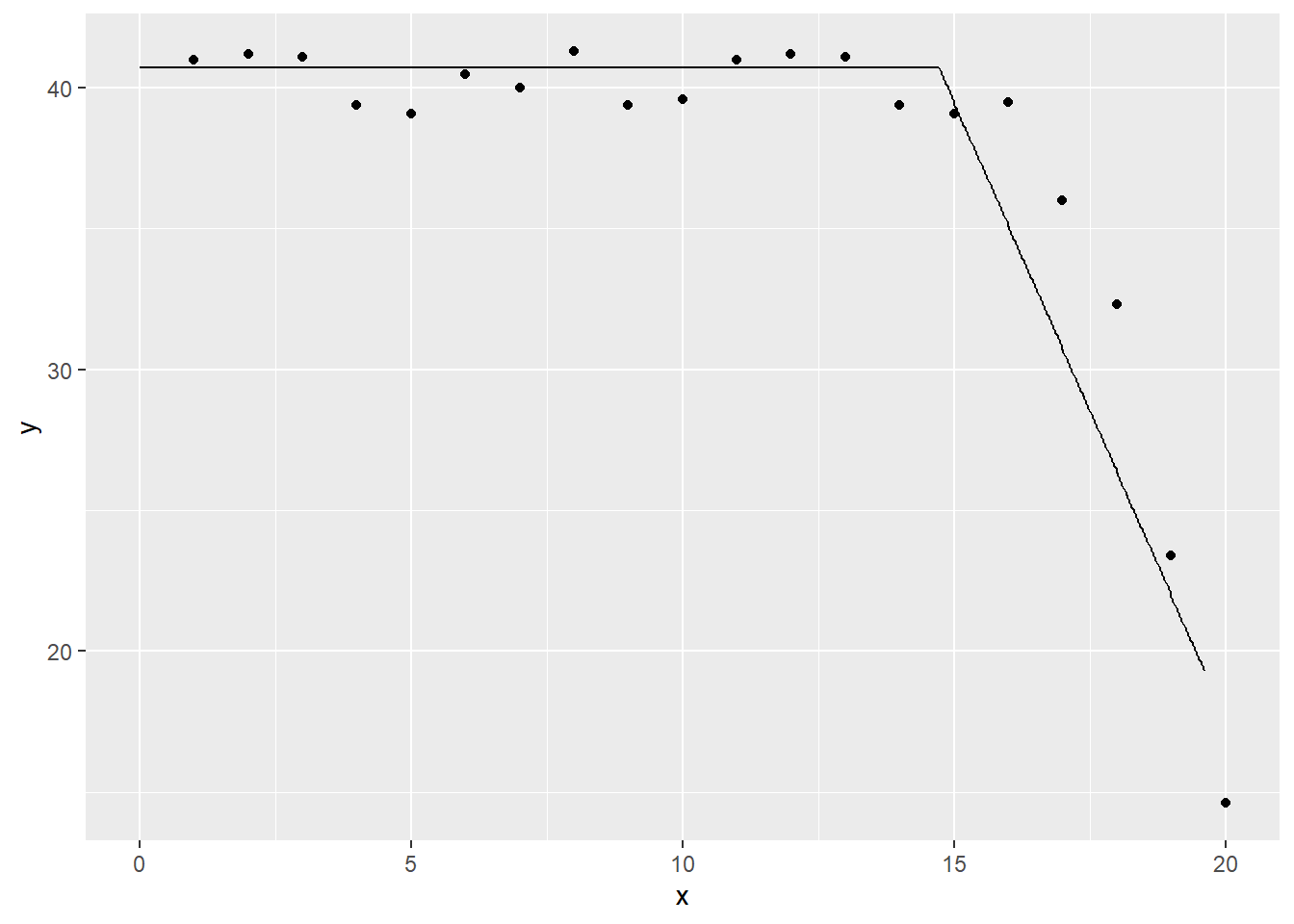

Fit a linear spline

I want a function that is flat for the values x = 0 to 15, and that drops linearly for x > 15. I also want to function to be continuous (no abrupt jumps).

To fit this function, you need a special X matrix.

linear_spline_ivs <- data.frame(x0=rep(1, 20), x1=c(rep(0, 15), 1:5))

linear_spline_ivs## x0 x1

## 1 1 0

## 2 1 0

## 3 1 0

## 4 1 0

## 5 1 0

## 6 1 0

## 7 1 0

## 8 1 0

## 9 1 0

## 10 1 0

## 11 1 0

## 12 1 0

## 13 1 0

## 14 1 0

## 15 1 0

## 16 1 1

## 17 1 2

## 18 1 3

## 19 1 4

## 20 1 5Surprisingly, even though the function you are trying to fit is not a linear function of x, you can still fit it with the lm function, as long as you have the correct independent variable matrix.

simple_spline_data <-

data.frame(

x1=linear_spline_ivs$x1,

x=simulated_example$x,

y=simulated_example$y)

linear_spline_model <- lm(y~x1, data=simple_spline_data)

tidy(linear_spline_model)## # A tibble: 2 x 5

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) 40.7 0.527 77.3 3.70e-24

## 2 x1 -4.29 0.318 -13.5 7.42e-11To get the plot of predictions for this model and future models accurate, you need to create values between the existing values.

x_extra <- seq(0, 20, length=1000)

data.frame(

x=x_extra,

x1=pmax(0, x_extra-15),

x1sq=pmax(0, x_extra-15)^2) %>%

full_join(simulated_example, by="x") -> enhanced_datalinear_spline_predictions <- augment(linear_spline_model, newdata=enhanced_data)

ggplot(linear_spline_predictions, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(y=linear_spline_predictions$.fitted)## Warning: Removed 999 rows containing missing values (geom_point).## Warning: Removed 19 row(s) containing missing values (geom_path).

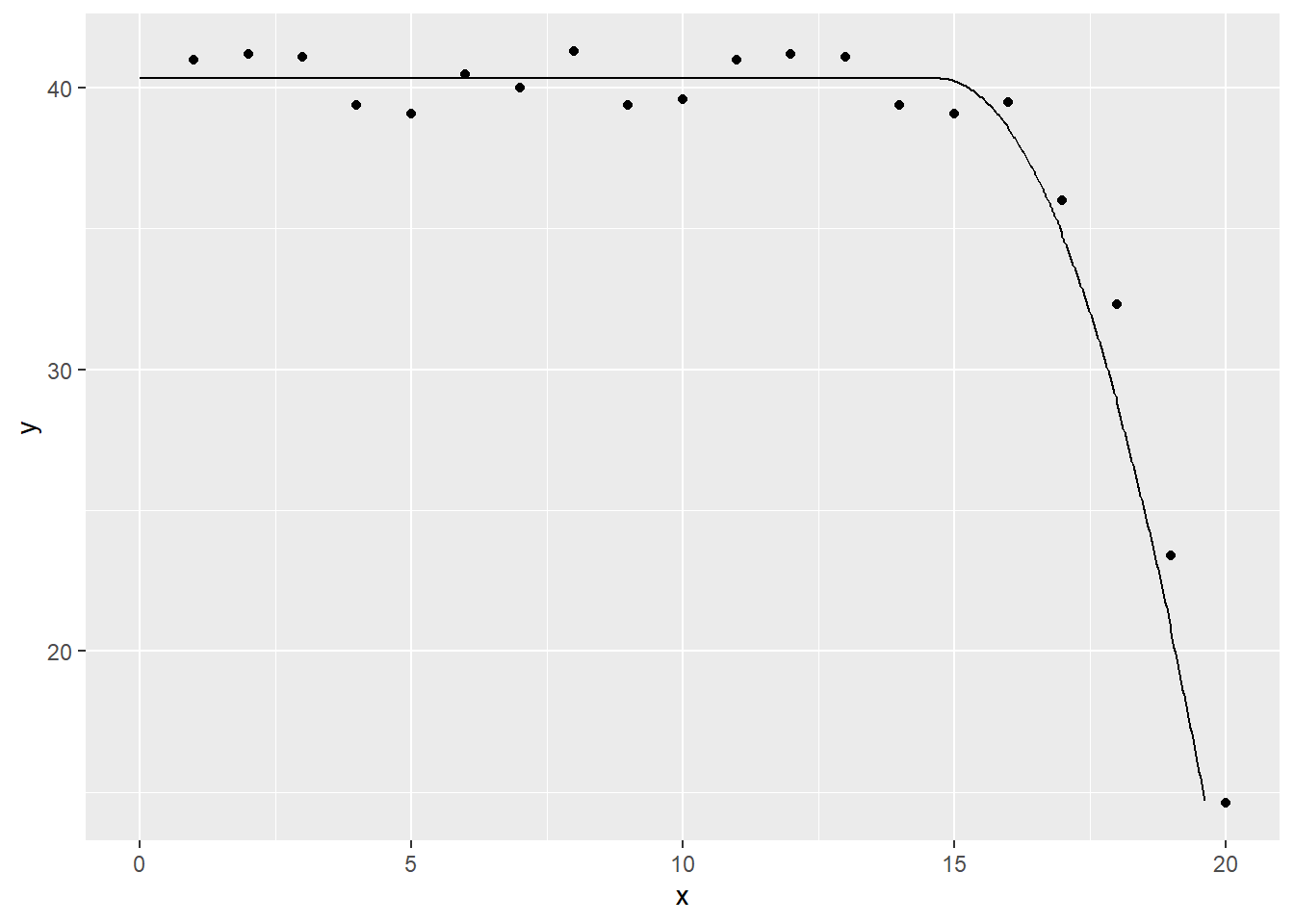

Fit a quadratic spline

Suppose you want to fit a function which is flat up to a certain point and then declines quadratically. You could do this with the following model.

simple_spline_data %>%

mutate(x1sq=x1*x1) -> quadratic_spline_data

quadratic_spline_model <- lm(y~x1sq, data=quadratic_spline_data)

tidy(quadratic_spline_model)## # A tibble: 2 x 5

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) 40.3 0.204 198. 1.69e-31

## 2 x1sq -1.03 0.0291 -35.2 4.64e-18quadratic_spline_predictions <- augment(quadratic_spline_model, newdata=enhanced_data)

ggplot(quadratic_spline_predictions, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(y=quadratic_spline_predictions$.fitted)## Warning: Removed 999 rows containing missing values (geom_point).## Warning: Removed 19 row(s) containing missing values (geom_path).

Notice that the quadratic model is smoother. It does not have a sharp elbow at the transition. Smoothness is often preferred in model fitting, though there are exceptions.

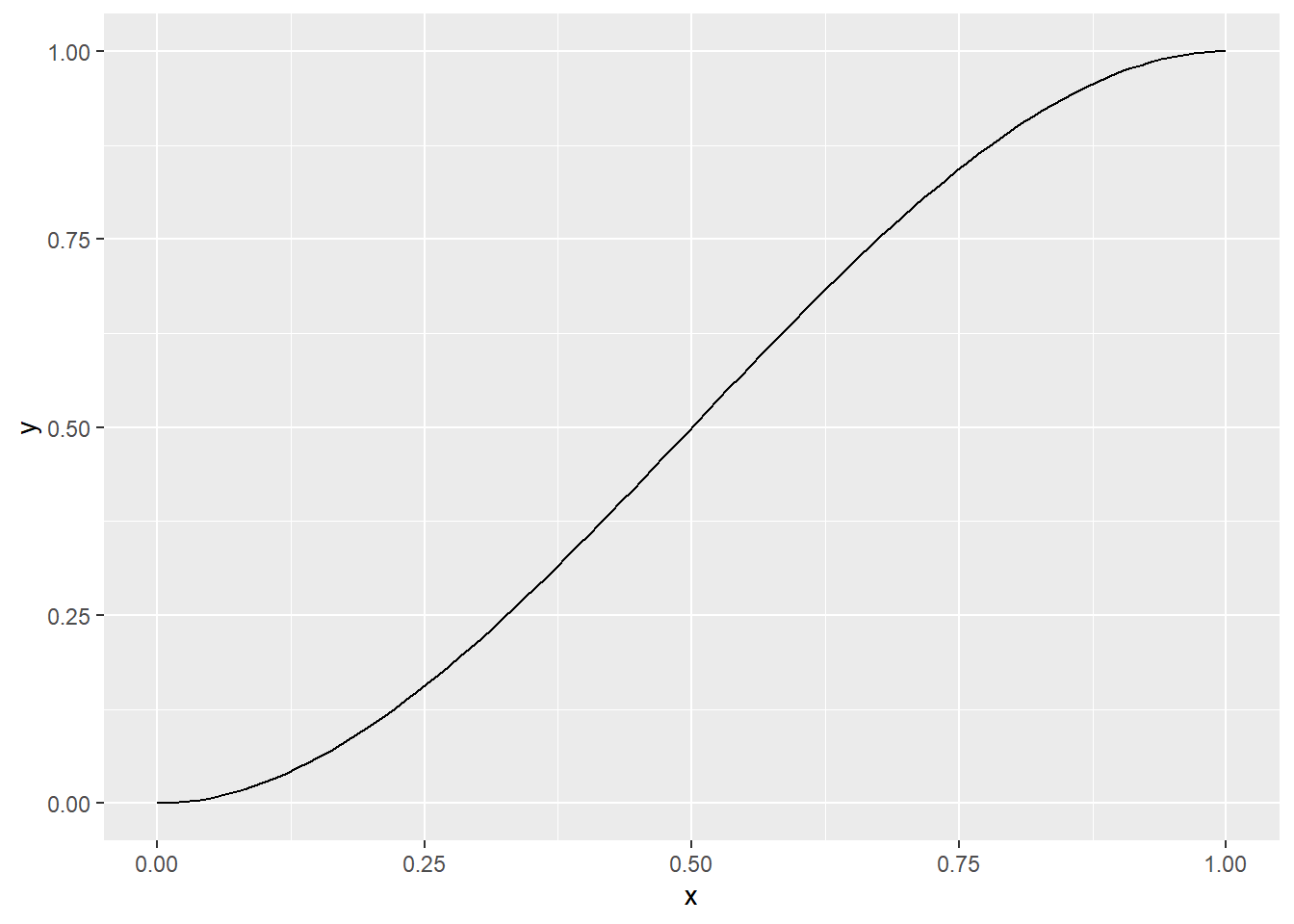

Fit a cubic spline

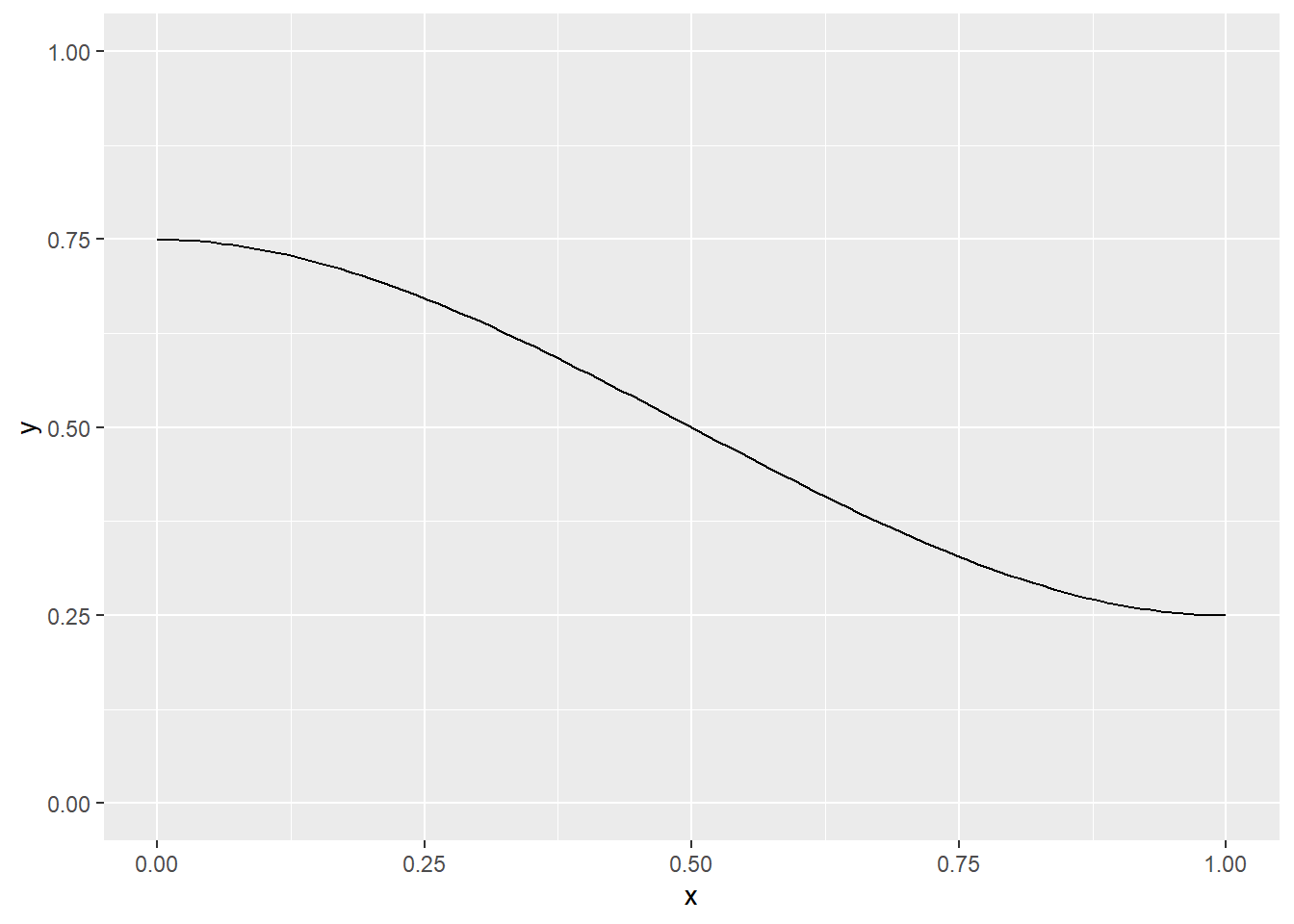

Here’s a final example of very simple splines. There is a “magic” cubic polynomial, \(3x^2-2x^3\). It rises smoothly from 0 at x=0, to 1 at x=1. It is flat (zero first derivative) at x=0 and x=1. This is what the function looks like.

x <- seq(0, 1, length=100)

y <- 3*x^2-2*x^3

data.frame(x=x, y=y) %>%

ggplot(aes(x, y)) +

geom_line()

You can add a constant and/or multiply by a constant to get different starting and ending points. So, for example,

\(0.75 - 0.5(3x^2-2x^3)\)

will start at 0.75 and drop 0.5 units to end at 0.25.

x <- seq(0, 1, length=100)

y <- 3*x^2-2*x^3

data.frame(x=x, y=y) %>%

mutate(y=0.75-0.5*y) %>%

ggplot(aes(x, y)) +

geom_line() +

expand_limits(y=0:1)

I will use this function to show transition probabilities in a graph.

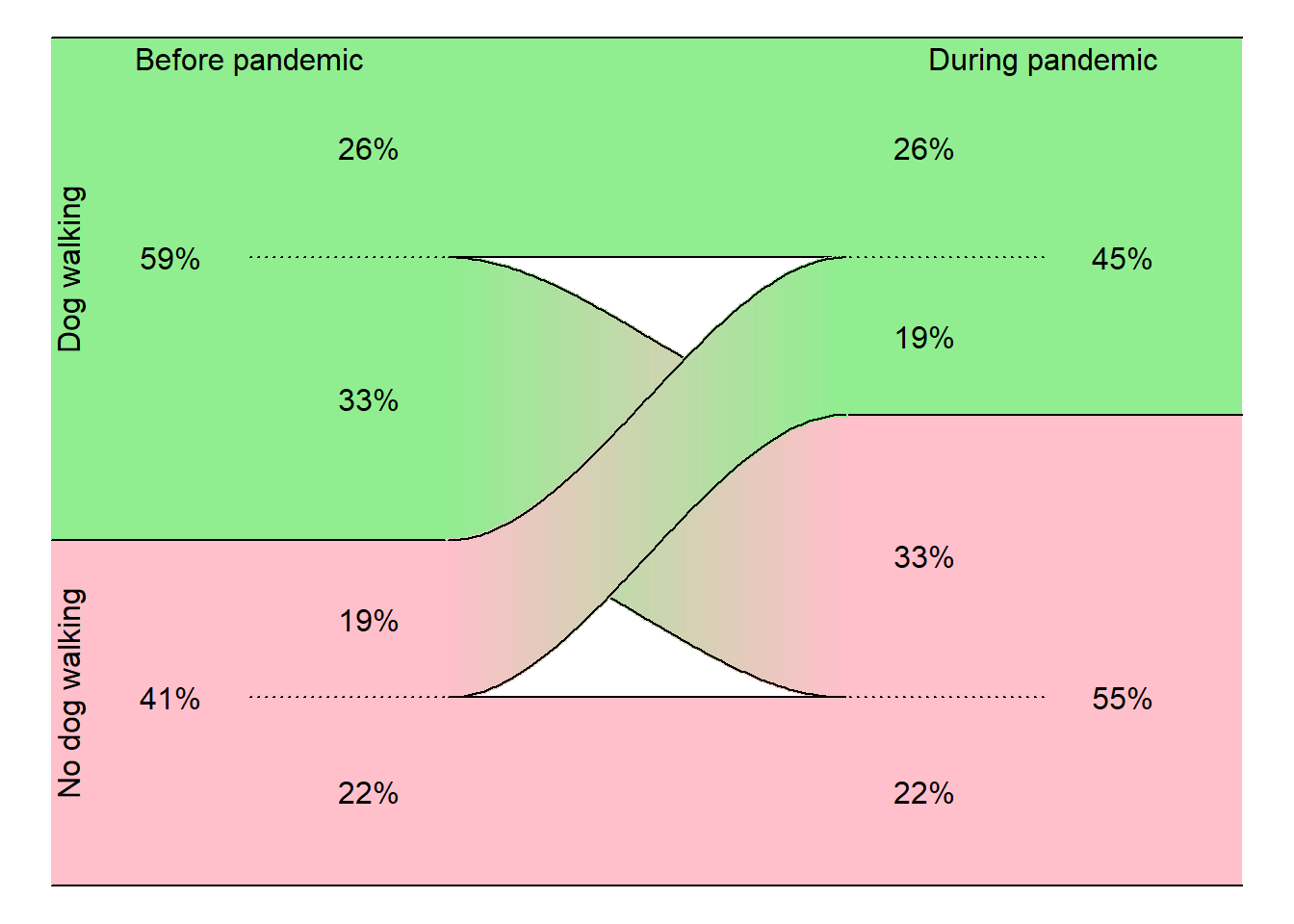

In a study of dog walking. Data was collected before and during the COVID pandemic. A “dog walker” was classified as someone who spent 150 minutes or more per week walking their dog. Did the proportion of dog walkers increase or decrease during the pandemic?

Source: Wallengren O, Bosaeus I, Frändin K, Lissner L, Falk Erhag H, Wetterberg H, Rydberg Sterner T, Rydén L, Rothenberg E, Skoog I. Comparison of the 2010 and 2019 diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) in two cohorts of Swedish older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021 Oct 26;21(1):600. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02533-y. PMID: 34702174; PMCID: PMC8547086. Available in [html format][wal1] or [pdf format][wal2].

Here’s the data.

During

Pandemic

Before

Pandemic Dog walker Non-walker Total

Dog walker 56 72 128

Non-walker 40 48 96

Total 96 120 216Let’s convert these to cell percentages.

During

Pandemic

Before

Pandemic Dog walker Non-walker Total

Dog walker 26% 33% 59%

Non-walker 19% 22% 41%

Total 45% 55% 100%Vucinic M, Vucicevic M, Nenadovicć K. THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AFFECTS OWNERS WALKING WITH THEIR DOGS. J Vet Behav. 2021 Oct 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2021.10.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34690614; PMCID: PMC8527592. Avialble in html format or pdf format.

par(mar=rep(0.1,4))

plot(c(-1,2), c(0, 216), type="n", axes=FALSE, xlab="", ylab="")

polygon(x=c(-1, 0, 0, -1), y=c( 0, 0, 88, 88), col="pink", border=NA)

polygon(x=c( 2, 1, 1, 2), y=c( 0, 0, 120, 120), col="pink", border=NA)

polygon(x=c( 0, 1, 1, 0), y=c( 0, 0, 48, 48), col="pink", border=NA)

polygon(x=c(-1, 0, 0, -1), y=c(216, 216, 88, 88), col="lightgreen", border=NA)

polygon(x=c( 2, 1, 1, 2), y=c(216, 216, 120, 120), col="lightgreen", border=NA)

polygon(x=c( 0, 1, 1, 0), y=c(216, 216, 160, 160), col="lightgreen", border=NA)

segments(-1, 0, 2, 0)

segments(-1, 216, 2, 216)

segments(-1, 88, 0, 88)

segments( 1, 120, 2, 120)

segments(-0.5, 48, 0, 48, lty="dotted")

segments(-0.5, 160, 0, 160, lty="dotted")

segments( 1.5, 48, 1, 48, lty="dotted")

segments( 1.5, 160, 1, 160, lty="dotted")

x <-seq(0,1, length=100)

y <- 3*x^2-2*x^3

for (i in 1:length(x)) {

segments(x[i], 160-40*y[i], x[i], 88-40*y[i], col=rgb(floor(colorRamp(c("lightgreen", "pink"))(x[i]))/255), lwd=3)

}

lines(x, 88 - 40*y)

lines(x, 160 - 40*y)

lines(x, 160 + 0*y)

for (i in 1:length(x)) {

segments(x[i], 48+72*y[i], x[i], 88+72*y[i], col=rgb(floor(colorRamp(c("pink", "lightgreen"))(x[i]))/255), lwd=3)

}

lines(x, 48 + 0*y)

lines(x, 48 + 72*y)

lines(x, 88 + 72*y)

text(-0.95, 49, "No dog walking", srt=90)

text(-0.95, 157, "Dog walking", srt=90)

text(-0.5, 210, "Before pandemic")

text( 1.5, 210, "During pandemic")

text(-0.7, 48, "41%")

text(-0.2, 24, "22%")

text(-0.2, 68, "19%")

text( 1.2, 24, "22%")

text( 1.2, 84, "33%")

text( 1.7, 48, "55%")

text(-0.7,160, "59%")

text(-0.2,188, "26%")

text(-0.2,124, "33%")

text( 1.2,188, "26%")

text( 1.2,140, "19%")

text( 1.7,160, "45%")

Notice how the 19% slides smoothly upward and the 33% slides smoothly downward. So you can see that while some people took up dog walking during the pandemic, this was more than offset by the number who dropped dog walking during the pandemic.

Aris Perperoglou, Willi Sauerbrei, Michal Abrahamowicz, Matthias Schmid. A review of spline function procedures in R. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2019-03-06, 19(46). Available in html format or pdf format.